Hirakud juggles between human needs & environment protection

Sambalpur: Hirakud Reservoir, one of India’s largest man-made wetlands and a recently designated Ramsar site, stands between conservation success and mounting environmental challenges.

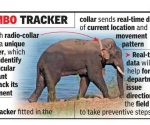

Sprawling across 700 sq km, this massive water body straddling Sambalpur, Bargarh, and Jharsuguda districts has transformed into a vital ecosystem since its construction across the Mahanadi.The reservoir not only generates 350 MW of hydropower and irrigates 436,000 hectares of farmland but also serves as a lifeline for the region’s rich biodiversity. “The wildlife thrives here because of Hirakud reservoir. They depend on its water for survival,” says Anshu Pragyan Das, divisional forest officer of Hirakud wildlife division. The reservoir borders Debrigarh sanctuary, home to diverse wildlife, including bison, leopards, and elephants. It also hosts over 3,70,000 migratory birds of 120 species annually, making it a crucial stopover for birds en route to Chilika lake.

Conservation efforts have shown promising results. In 2022-23, authorities removed 100 km of invasive Ipomoea weeds, replacing them with animal-friendly cynodon and chloris grasses. The wildlife division has also launched innovative programmes like “Debrigarh 48” to promote environmental awareness among students from 48 nearby villages.

Local communities are increasingly embracing conservation. Govindpur Birds Village exemplifies this shift, where former poachers have become protectors of avian visitors. Tourism is flourishing too, with eco-friendly initiatives like the Island Café on Bat Island drawing visitors from across the globe. Last year alone, over 70,000 tourists visited the sanctuary and wetland.

However, serious challenges threaten this ecological haven. Industrial fly ash from nearby factories and agricultural pesticides are polluting the reservoir’s waters. “Plastic pollution is a major concern,” says Ranjan Panda, known as the Water Man of Odisha. “Tourists litter picnic spots, affecting the reservoir’s beauty and ecosystem,” he said.

Inter-state water disputes add another layer of complexity. The reservoir’s water level depends on Chhattisgarh’s Kalma barrage, and polluted water released upstream affects Hirakud’s ecosystem. “The conflict between Odisha and Chhattisgarh over water release needs urgent resolution,” Panda emphasizes.

The reservoir also supports over 7,000 fishermen’s livelihoods, but the impact of cage culture fishing on water quality remains understudied. Experts stress the need for comprehensive research to address these emerging challenges and maintain Hirakud’s ecological balance.

As this vital wetland faces mounting pressures, the success of conservation efforts will depend on balancing human needs with environmental protection, making Hirakud a test case for sustainable wetland management in India.

Sprawling across 700 sq km, this massive water body straddling Sambalpur, Bargarh, and Jharsuguda districts has transformed into a vital ecosystem since its construction across the Mahanadi.The reservoir not only generates 350 MW of hydropower and irrigates 436,000 hectares of farmland but also serves as a lifeline for the region’s rich biodiversity. “The wildlife thrives here because of Hirakud reservoir. They depend on its water for survival,” says Anshu Pragyan Das, divisional forest officer of Hirakud wildlife division. The reservoir borders Debrigarh sanctuary, home to diverse wildlife, including bison, leopards, and elephants. It also hosts over 3,70,000 migratory birds of 120 species annually, making it a crucial stopover for birds en route to Chilika lake.

Conservation efforts have shown promising results. In 2022-23, authorities removed 100 km of invasive Ipomoea weeds, replacing them with animal-friendly cynodon and chloris grasses. The wildlife division has also launched innovative programmes like “Debrigarh 48” to promote environmental awareness among students from 48 nearby villages.

Local communities are increasingly embracing conservation. Govindpur Birds Village exemplifies this shift, where former poachers have become protectors of avian visitors. Tourism is flourishing too, with eco-friendly initiatives like the Island Café on Bat Island drawing visitors from across the globe. Last year alone, over 70,000 tourists visited the sanctuary and wetland.

However, serious challenges threaten this ecological haven. Industrial fly ash from nearby factories and agricultural pesticides are polluting the reservoir’s waters. “Plastic pollution is a major concern,” says Ranjan Panda, known as the Water Man of Odisha. “Tourists litter picnic spots, affecting the reservoir’s beauty and ecosystem,” he said.

Inter-state water disputes add another layer of complexity. The reservoir’s water level depends on Chhattisgarh’s Kalma barrage, and polluted water released upstream affects Hirakud’s ecosystem. “The conflict between Odisha and Chhattisgarh over water release needs urgent resolution,” Panda emphasizes.

The reservoir also supports over 7,000 fishermen’s livelihoods, but the impact of cage culture fishing on water quality remains understudied. Experts stress the need for comprehensive research to address these emerging challenges and maintain Hirakud’s ecological balance.

As this vital wetland faces mounting pressures, the success of conservation efforts will depend on balancing human needs with environmental protection, making Hirakud a test case for sustainable wetland management in India.