Gender-blindness: A threat to TN women in unorganised workforce | Chennai News – The Times of India

From musculoskeletal disorders to vision loss, women in fishing, garment sectors face challenges that fall outside purview Of occupational health hazards code

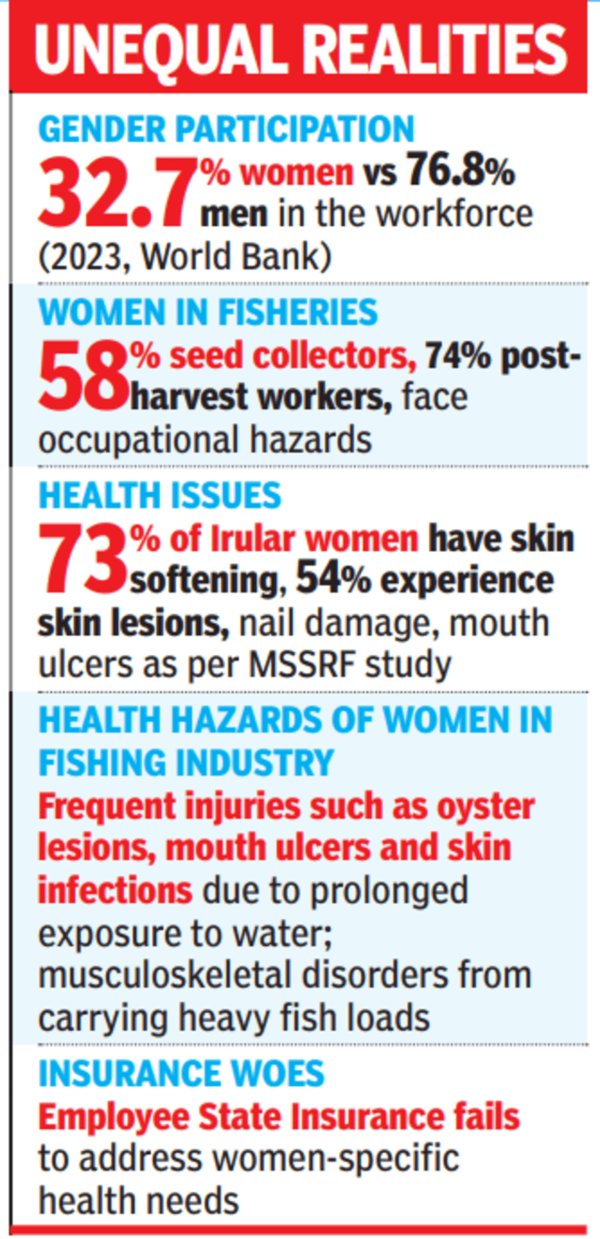

India has a significant gender gap in labour force participation, with 32.7% for women and 76.8% for men, as per World Bank data of 2023. India’s informal sector employs more than 90% of the workforce, with fisheries playing a key role in the economy.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) classifies fishing as one of the most dangerous jobs, but fisherwomen’s specific vulnerabilities remain unrecognised. Women make up 58% of seed collectors and 74% of post-harvest workers, yet they face occupational hazards without social protection. Health risks for women workers in the informal sector, especially fisherwomen, are largely invisible.

Fisherwomen, particularly from marginalised communities, work in unsafe conditions without basic infrastructure. At landing centres, harbours, and fish markets, amenities such as toilets and drinking water are absent, leading to hygiene issues, UTIs, and reproductive health problems.

A study by MS Swaminathan Research Foundation (MSSRF) in Chennai found that fisherwomen involved in street vending and head-loading suffer from prolonged exposure to sunlight, causing headaches, skin irritation, sunburn, and vision problems. Carrying heavy fish loads leads to musculoskeletal disorders.

Kanjana, a 40-year-old Irular tribal fisherwoman, who spent 15 years hand-picking prawns in the Pichavaram backwaters of Tamil Nadu, endured frequent injuries, such as oyster lesions and catfish stings. She was anaemic and suffered skin infections due to prolonged exposure to water.

MSSRF initiated a participatory trial to find suitable protective gear, and after some experimentation, a specialised, flexible gumboot was introduced, reducing foot injuries, blood loss, and discomfort.

A study on 250 Irular tribal fisherwomen in the region found 73% experienced skin softening from prolonged water exposure, while 54% had skin lesions, fingernail damage, and mouth ulcers.

As these women are not officially recognised as workers, their health issues fall outside occupational health frameworks. Many only seek medical help when their conditions affect their work. They rely on public health facilities in fishing communities as private healthcare is unaffordable to this community of women. But these issues are often undiagnosed and unattended.

The textile and garment industry too has increased women’s labour participation, with more than 60% of workers being women. However, it has also harmed their health. Long hours in fixed postures lead to musculoskeletal disorders, while skin and respiratory diseases are common.

Many women suffer from kidney stones, UTIs, menstrual irregularities, and reproductive health issues due to limited access to toilets, water, and harsh work conditions.

Balancing work and household duties, often skipping meals, leads to malnutrition and anaemia. Despite formal sector employment, women lack access to clean water, toilets, and sanitary napkins, with conditions worsening in peak summer.

They also face verbal and sexual abuse, as well as mental health challenges. The demanding nature of the work often forces women to leave the industry for pregnancy and subsequently for health issues.

The paid and unpaid work of most women exposes them to specific health risks. Women in industries such as garments and fisheries contribute to economic productivity but lack health security.

Their risks arise from biological factors (pregnancy, menstruation) and gender-based inequalities (discrimination, harassment, limited opportunities), along with gender-blind labour and health systems. WHO recognises work-related stressors, such as excessive workload and unsafe conditions, as mental health risks.

Many stressors such as physical strain, long hours, and mental stress do not fit the “imminent danger” definition under the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions (OSHWC) code, 2020. Efforts by govt and private sector to bridge this gap include incentives for education, skilling, maternity benefits, childcare facilities, equal pay, and workplace safety measures. However, women’s health, in all its physical, mental, and social dimensions, has not been prioritised as a fundamental right of a woman worker.

Accessing healthcare and sickness benefits through the Employees’ State Insurance (ESI) system is fraught with challenges. ESI dispensaries are underutilised and do not address women’s occupational health issues, due to factors like a lack of women doctors, long wait times, inadequate training, and biased provider attitudes.

There is no systematic collection of gender or occupation disaggregated data, and gendered barriers, such as mobility restrictions and caregiving duties, further limit access.

Consequently, many women turn to private healthcare, leading to high out-of-pocket expenses and worsening health. With the rise in non-communicable diseases (NCDs) among women, the burden on low-income households is growing. As part of women’s wages are deducted for ESI, this underutilisation not only wastes resources but also violates their right to health.

The ESI system, designed for male workers, fails to address women’s specific health issues. Public healthcare lacks gender-sensitive approaches and private care is often unaffordable, causing women to forgo treatment, worsening their conditions. To ensure that women enjoy the highest attainable health standards, systemic changes are necessary. Occupational health policies must integrate gender-specific risk factors and address preventive, promotive, and primary care measures. Essential facilities such as clean toilets, sanitary napkins, drinking water, and heat-adapted work timings should be mandatory in formal and informal sectors.

Employers should be accountable for creating stress-free work environments and providing healthy wages that allow women to prioritise their health. Workplaces should be the starting point for primary healthcare. Facilities, from primary health centres to district hospitals, should be trained to recognise gender-specific work-related health issues.

The ESI system must be restructured with gender-sensitive doctors and counsellors, providing comprehensive services, including mental health support and care for gender-based violence.

Informal sector workers should also have access to ESI, with govt support to cover costs. Gender-disaggregated data collection is essential for identifying occupational health trends and informing policy decisions. Research institutions should establish specialised centres to study gendered occupational diseases and develop appropriate interventions.

Strengthening occupational safety, health, and rights for women workers will lead to a more inclusive and empowering work environment in India. But addressing these critical gaps needs collaboration between policymakers, employers, healthcare providers, and women workers.

(Rajalakshmi RamPrakash is Consultant (Gender), MSSRF; S Velvizhi is Area Director at MSSRF)

Email your feedback to southpole.toi@timesofindia.com